Mughals was a peripatetic court moving according to the policy dictates of the times. Since they came from unsettled Central Asia therefore they exhibited tremendous urge to ensure their control over vast domains they ruled in India.

They were hands-on rulers crisscrossing the length and breadth of the subcontinent never staying at one point for long periods of time. It was Akbar who created an itinerant court and during the course of his fifty years on the Mughal throne he moved from one place to the other with the result that Agra, Fatehpur Sikri, Lahore and Delhi in turn served as the capitals of the Empire.

His policy was emulated by the emperors following him and it became an essential characteristic of the Mughal rule. The travels all across India made Mughal rule extremely dynamic whose ruling class consistently pursued a policy of networking through moving throughout the country. It was very mobile and never hesitated from reaching the far flung corners of the Empire.

Mughal military strategies, political structure, and urban form owed much to Central Asian traditions though under innovative leadership the Mughals developed new organisational forms that were uniquelySouth Asian, produced from a creative usage of indigenous Muslim and local traditions and largely acquired through their incessant travels across their domains. Mughal elite kept on looking for opportunities to visit the locally appointed rulers and kept in touch with local traditions.

At the fore front of this exercise was the Emperor himself who was frequently found travelling his vast domains and remained in constant touch with the governors he appointed in different areas. The Mughal emperor was very vigilant about his empire and took pains to travel to the far-flung areas of the subcontinent just to ensure his subjects that he was looking after their interest.

Travel was an essential part of imperial governance dutifully pursued by the itinerant Emperor who always wanted to stay ahead of the rest of the governing class. He thought it imperative to be physically present amongst his subjects and tried solving their problems on the spot.

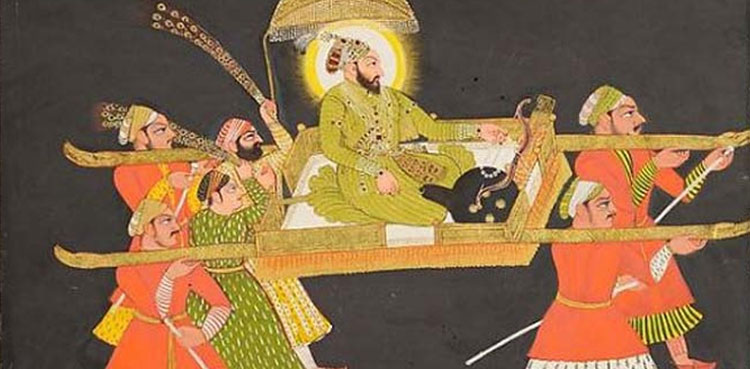

The most dramatic example of the Mughal mobile capital was the imperial camp. Originating in the small highly mobile military camps of Babur, the elaboratelater imperial camp was established by Akbar in the late sixteenth century andwas used by all subsequent Mughal rulers. Keeping in view the imperial dignity and convenience the imperial establishment undertook maximum measures to keep the visits worth their while. His travel train was highly decorous and full of luxuries suiting his station.

Two main categories of camps existed: small ones used on short journeys or for hunting parties and large camps constructed for royal tours and military expeditions. By the late seventeenth century, these large camps containedup to 300,000 individuals.The emperor entourage was representative of the imperial grandeur and it was the intention of the rulers to create as much impression on the subjects as possible.

From his imperial camp the emperor and his administrators carried out the main business ofgoverning their vast empire. The imperial postal system was equipped with every facility just to keep the emperor informed of whatever was happening in the country. The imperial camps were neither short-lived noroccasional phenomena. They catered to an official policy designed to serve the imperial purpose. It was calculated that from 1556 to 1739 Mughal emperors spent nearly 40 per cent of their time in camps on tours oftenlasting a year or longer. At different times the Mughal emperor was travelling from one part to the other of his territories. The imperial camp, also known as the exalted or victorious camp, was constructed according to a formal plan, described as a mobileversion of Akbar’s capital of Fatehpur Sikri.

A large wall of cloth screens enclosed the royal camp, fanning an east-west oriented rectangle nearly 1,400 metres long. The emperor’s tent and royal reception areas were consistently placed in the center of the eastern end of the royal enclosure. His was the only two-storied tent in the imperial camp, enclosed within walls of distinctive scarlet cloth. Next to the emperor was a screened area containing the tents of the royal harem and beyond this were enormous awnings for public and private royal audiences. Tents for nobles were aligned in carefully specified locations that spatially expressed their relations with the ruler.

Beyond the royal enclosure were the tents of lesser nobles and the military, as well as administrative facilities, stables,arsenals, workshops of attached specialists and kitchens. Merchants and moneylenders fanned neat bazaar areas along the streets of the massive tent city.

Imperial coinage was also issued from the camp mint as is borne out during Akbar’s reign detailing low-valuecopper coins and the name of the town nearest the imperial camp.Inscriptions on gold and silver coins were explicitly linked with the camp itself attesting to royal acknowledgment of the centrality of the imperialcamp. This tradition was kept alive by most emperors and these commemorative coins became part of the imperial coinage.

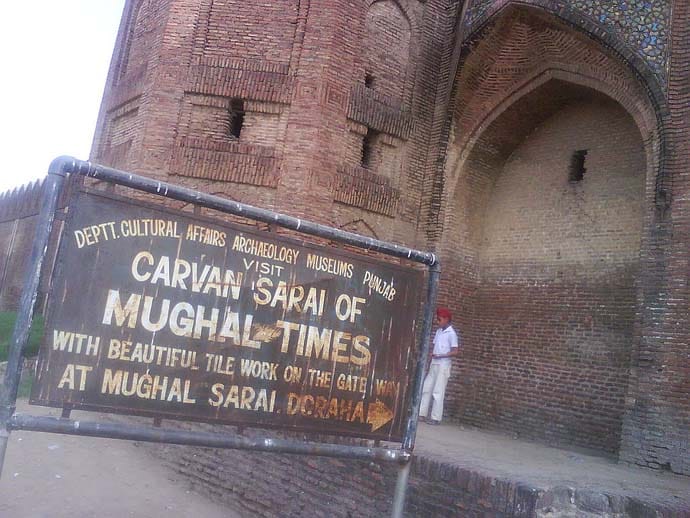

The logistical challenges of moving and provisioning hundreds of thousands of people and the 50,000 horses and oxen required to transport tents, baggage and equipment were considerable. Far from a rapid military strike force, the camp seldom traveled more than16 km per day and was preceded by royal agents, scouts andlabourers who prepared roads and bridges, selected campsites, arranged the purchase of foodstuffs and fuel and assured the cooperation of local rulers. The camps were constructed by more than 2,000 soldiers and labourers sent on ahead of the main imperial party; two complete sets of all tents and facilities were thus required. Local merchants and farmers were encouraged tobring their produce to the markets at the camps; foodstuffs may also have beenobtained from imperial or civic stores in towns near the camp sites.

When the emperor was resident in his camp, it was there that the bulk of imperial administrative activities occurred and important decisions were made. The imperial camp was the de facto capital, and a significant portion of the resident population of the constructed capital cities appears to have accompanied the emperor in his travels. The mobile imperial camp no doubt played many roles in Mughal political and economic life. It made possible the movement of enormous military forces throughout the empire and to strategic areas where imperial control was weakor threatened, while simultaneously providing facilities and personnel for essential administrative activities.

The massive display of imperial grandeur of the encampments and of the formal marches must have had considerable impact on subject populations.

Rather than a distant or seldom-seen figure ensconced in a protected capital, the Mughal emperor and his royal household could be seen and venerated by large segments of the population as his camp traveled through imperial territories. Although the pattern of movement appears to have been largely determined by political and military concerns, a further consequence of the imperial camp was to bring large numbers of people and animals to available resources, thus decreasing the costs of transporting foodstuffs and fuel to the cities.

Imperial camps usually left a lasting impression on the sites they were held and their inhabitants entertained their cherished memories for a long time.

source https://arynews.tv/mughal-travel-mode-blog/

0 Comments